Webwords 61: Entrepreneurship and Speech-Language Pathology - July 2018

Generally speaking, an entrepreneur is someone who, or more specifically in Economics an entity that, organizes, manages, and accepts the risks, challenges and responsibilities of a business or enterprise.

For most of we speech-language pathologists/speech and language therapists (SLPs/SLTs) in private or independent practice, saying that we are entrepreneurs is like donating a thousand smackers (or quid, or bucks) to a good cause and saying you are a philanthropist. But to succeed in the marketplace—and let's face it, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), more than 60 percent of small businesses cease operations fewer than three years after starting—you have to think like an entrepreneur. Otherwise, you may feature (anonymously, of course), in the next Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) report into corporate insolvencies. In their 2016-2017 report, ASIC nominated its top three reasons that businesses failed: 46% suffered poor strategic management, 47% had inadequate cash flow or high cash use, and 35% had poor financial control including lack of records.

Etymology

As a loan word from French, entrepreneur is thought to have originated from the Latin: entre, to swim out, and prendes, to grasp, take hold of, understand, or capture. It evolved into the Old French agent noun, entreprendre (undertake), crossed the channel as entreprenour in 17th century Middle English, but then fell into disuse. It re-emerged in the early 1800s as entrepreneur, denoting 'the director of a musical institution' in French, and 'a manager or promoter of a theatrical production' in English, gradually acquiring its modern English connotation of 'business manager' and 'risk-taker' or 'adventurer'.

In the 21st century, entrepreneur is applied in various ways. At one end of the scale it signifies individuals who are small business owner-operators, and 'entities' with the ability to find and act upon opportunities to translate inventions or technology into new products. At the other end it refers to anyone—even school children—relishing problem-solving and innovation.

Entrepreneurship is subdivided into pursuits such as ethnic minority entrepreneurship (involving self-employed business owners who belong to racial or ethnic minority groups, like Dion Devow and Berto Perez); social entrepreneurship (encompassing entities that work to increase social capital by founding social ventures, including charities, for-profit businesses with social causes, and other non-government organizations, such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and Fair Trade, and on a smaller scale the Thankyou Group and Who Gives a Crap); cultural entrepreneurship (think d.light and Barefoot Power), feminist entrepreneurship (for example, the Catherine Hamlin Fistula Foundation), institutional entrepreneurship (where a standout is Wikipedia, the seventh most-frequented website on the planet [Safner, 2016]), and project-based entrepreneurship (well represented by Water Aid, and the National Skill Development Corporation).

Among the new terms that have emerged are nascent entrepreneur: someone starting out with a venture idea; millennial entrepreneur: a Gen-Y-child-of-Baby-Boomers business owner, born between 1981 and 1997 (with the current age-range of 21 to 37), and raised using digital technology and mass media, for example, Mark Zuckerberg who was born in 1984 and whose net worth is US$62.2 billion; and entrepreneurial mindset. For the London Financial Times, entrepreneurial mindset refers to 'a specific state of mind which orientates human conduct towards entrepreneurial activities and outcomes. Individuals with entrepreneurial mindsets are often drawn to opportunities, innovation and new value creation. Characteristics include the ability to take calculated risks and accept the realities of change and uncertainty'.

Entrepreneurs, leaders, managers, and small business operators

Microsoft Word suggests synonyms for entrepreneur, that include: businessperson, tycoon, magnate, impresario, industrialist, financier, capitalist, and mogul—but interestingly, neither manager nor leader. The notions of entrepreneurship, management and leadership, however, are often conflated, provoking a terse tautology from Peter Drucker (1909-2005): 'the only definition of a leader is someone who has followers' (Drucker, 1992, p. 103). Gerson (2015) reinforces the point with: 'While the disciplines of Leadership and Management certainly contain a natural overlap in the skills needed to perform their respective functions, there are however clearly discernible attributes unique to each skill. Simply put, leaders lead and managers manage'.

The emphasis on entrepreneurs as leaders was evident over a decade ago, when Gascoigne (2006) made 15 recommendations in an RCSLT Position Paper, the last of which was, 'The challenges of the changing context mean that business and entrepreneurial skills sets will become more relevant for senior managers. Excellent communication and negotiation skills should also be developed by all speech and language therapy service leads as part of a portfolio of leadership competence. In order to respond as leaders in the changing context, SLTs should recognise the importance of key leadership skills. Service leads should not only ensure that they demonstrate these skills, but also encourage leadership development throughout the structures for which they are responsible.'

A further confusion is that entrepreneur is often used synonymously with small business operator, but whereas a small business operator manages risk and works to generate income, an entrepreneur takes a gamble, cultivates innovation, and strives for considerable wealth creation—potentially in the millions—over periods as short as five years.

What is a 'small business' in Australia?

ASIC regulates small proprietary companies with two out of the following three characteristics: (1) an annual revenue of less than AU$25 million, (2) fewer than 50 employees, and (3) consolidated gross assets of less than AU$12.5 million. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) defines a small business as one that has annual revenue turnover (excluding GST) of less than AU$2 million. Meanwhile, Fair Work Australia defines a small business as one that has fewer than 15 employees. Both ASIC and the ATO use, informally, the definition of small business preferred by the ABS, that is, a business that employs fewer than 20 people.

While most entrepreneurial enterprises begin as small businesses, not all small businesses are entrepreneurial. Many, such as most, if not all, speech-language pathology (SLP) private practices in Australia, are owner-operator sole-proprietor set-ups—with no, or a small number of employees—offering a tightly defined existing service (e.g., a clinical SLP service), product (e.g., SLP medico-legal consultancy) or process (e.g., SLP intervention via the Internet). They do so without aspiring to growth, whereas entrepreneurial undertakings offer innovation in the form of a service, product, or process characterised by an obvious element of risk, with the entrepreneur aspiring to strategically scale up the company by adding employees and seeking fresh sales opportunities nationally and abroad, in an enterprise financed by venture capital, private 'angel' investors, or bootstrap finance, and increasingly, crowd funding.

Successful entrepreneurs demonstrate the skill of leading a business along a positive course, through appropriate planning and adaptation to change, while recognising and accommodating their own strengths and limitations; exactly the same skills and qualities displayed by successful SLPs/SLTs in all work contexts (private and public), whether as administrators, academics, clinicians, consultants, or researchers.

Thin on the ground

Two quick web searches, for speech + pathologist + entrepreneur, and speech + therapist + entrepreneur, locate relatively few SLPs/SLTs who describe themselves, or are described by others, as successful entrepreneurs (Shatha Al Nassar, Jen Bjorem, Barbara Fernandes, Don Harris, Michelle Morrissey ( story), Elizabeth Schwartz and Sonu Sanghoee, Tammy Taylor (story), and some more in LinkedIn), but Webwords could locate only a handful like Rebecca Bright whose earnings were in the millions, or who aspired to significant growth or a global presence. Examples of those that fit the bill, with figures drawn from publicly accessible electronic documents, include Hear & Say Ltd (2017 income AU$6.5 million assets AU$15.8 million, 61 staff in five centres across Queensland, with outreach to India, and global professional training); the PROMPT Institute (five directors, four staff, 35 instructors functioning as independent contractors, across four continents; revenue US$14.7 million); TalkTools (sole proprietor, 16 employees, worldwide product distribution including 'training'; revenue US$14 million); and Therapy Box (two directors, 21 employees, turnover less than £2 million).

Learning to think like an entrepreneur

The number of US university entrepreneurship classes increased twenty-fold between1985 and 2015, and in Australia a range of university courses aimed at SLPs offer instruction in the necessary skills. For instance, Southern Cross University promises that Bachelor level SLP graduates will, 'develop an entrepreneurial and sustainable approach to clinical/professional practice utilising appropriate leadership and management skills'. On a promotional web page, Bachelor of Applied Science and Master of Speech Pathology students at La Trobe University are advised that, 'three Essentials—Global Citizenship, Innovation & Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Thinking—are specialist areas designed to give you an edge with employers. Essentials will enable you to adapt your knowledge and skills to new contexts in a rapidly changing world.' You can watch a brief video. In sum, 53 tertiary institutions in Australia offer entrepreneurship courses.

Last hurrah

It has been fun assuming the Webwords alter ego for the past twenty years, scouring the Internet for information and resources relevant to each ACQ, and then JCPSLP theme. Challenging too, delving into areas well beyond my direct experience as an SLP, but also interesting, intellectually stimulating and at different times, shocking, disheartening, surprising, poignant, and inspiring. Webwords has run its course and will be replaced in the next JCPSLP by a new column. One possibility the committee is considering is to invite a new non-SLP/SLT author each time to explore an issue's theme from their important perspective: as client, collaborator, colleague, family member, friend, manager, policy-maker, and Jo and Joe Public. Their collective experiences, insights, evaluations, understandings and 'different slants' on what we do, hold the capacity to enhance professional practice. As a foretaste of what might be in store for JCPSLP readers, Webwords' final Internet suggestion is Lyn Stone's exquisite (and moving) piece about her daughter Chloe, who died peacefully in her sleep on April 12, 2018. It's called My non-verbal child: it doesn’t get any better than this.

References

Drucker, P. F. (1992). Managing for the Future: the 1990's and Beyond, London, UK: Routledge.

Gascoigne M. (2006). Supporting children with speech, language and communication needs within integrated children’s services: RCSLT Position Paper, London: RCSLT. DOWNLOAD

Gerson, E. (2015). Leadership versus Management. Retrieved 9 April, 2018 from ToolsHero: https://www.toolshero.com/management/leadership-versus-management READ

Safner, R. (2016). Institutional entrepreneurship, wikipedia, and the opportunity of the commons. Journal of Institutional Economics, 12(4), 743-771. ABSTRACT

Links

8 Podcasts Every Entrepreneur Should Follow in 2018

ABS: Services we provide to small business

David Kinnane: Speech pathologists: how to build ethical, profitable, high quality private practices that outlast us

Employability skills

Entrepreneur (in the Sydney Morning Herald)

Peter Drucker: Father of post-war management thinking

Simple access to information and services for business

So, you want to work in a private SLP practice in Australia? Interview tips from @WeSpeechies!

The myth of the millennial entrepreneur

Top tips to start or grow your own business

Why read Peter Drucker? Harvard Business Review

Women in STEM and entrepreneurship grants

Webwords 60: Developmental Language Disorder: #DevLangDis - March 2018

Developed by RAND in the 1950s, the “deliberative tool” called the Delphi method is a forecasting technique, in which a panel of selected experts responds anonymously, in writing, to two or more rounds of carefully designed questionnaires. Following each round, panellists' input is aggregated by moderators (or facilitators) and then shared with the whole group. The experts, who usually include actors and stakeholders, and who may be geographically near to, or distant from each other, consider the views of the other panellists and are free to maintain, change, expand, or fine-tune their answers in successive rounds. Through this iterative process of co-construction, the panel endeavours to reach a common position, facilitating the creation of innovative solutions to complex problems.

The rapturous marketing hype, for open source and commercially available e-Delphi software, commonly promises unanimity, with glib slogans like “better solutions through collective intelligence” and “a proven way to harness wisdom”, but as Cole, Donohoe, and Stellefson (2013) caution researchers, survey iteration can end in disagreement and no consensus.

CATALISE

Through dedication and persistence, CATALISE, the 2016-2017 multiple part Delphi into children with unexplained language problems, led by Dorothy Bishop, did not suffer such a disappointing fate. Between them, two facilitators and 57 panellists maintained enthusiasm for the project, achieving 80% consensus around key goals. They also gained new perspectives on international and interdisciplinary viewpoints and concerns, while pinpointing areas of indecision, such as uncertainty among ASHA members over the wisdom and practicality of abandoning the term Specific Language Impairment (SLI) in favour of Developmental Language Disorder (DLD)...or not.

The panel began with the people who were asked to write commentaries for an International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders special issue on The SLI Debate (Ebbels, 2014) and all co-authors of articles therein, except for the Delphi moderators, psychologists Dorothy Bishop and Maggie Snowling. Ebbels, 2014, and Bishop et al., 2016, highlight the reasons for, and pitfalls of division around terminology for language disorders, building towards the Bishop et al., 2017 proposal for standard definitions and nomenclature to be applied around the world.

The experts were drawn from ten disciplines or agencies (including Audiology, Charities, Child Psychiatry, Education, Paediatrics, Psychiatry, and Psychology, with a predominance of SLP/SLT clinicians and/or researchers) from the six MRA signatory countries: Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, the UK and the US. Their goal in phase one, round one (Bishop, Snowling, Thompson, Greenhalgh, and The CATALISE Consortium, 2016) was to work towards agreed criteria for identifying children with language disorders who might benefit from specialist services. Accord was reached in round two, resulting in a consensus statement, a summary of relevant evidence, and a commentary on residual disagreements and gaps in the evidence base (Bishop, et al., 2016).

Diagnosing and describing DLD

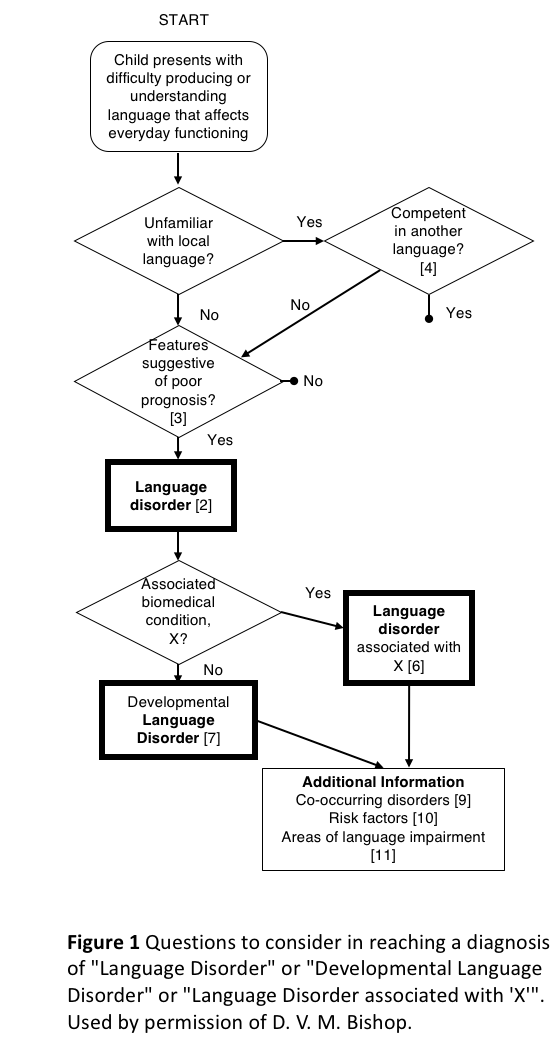

Questions to consider in reaching a diagnosis of “Language Disorder” or “Developmental Language Disorder” or “Language Disorder associated with X”, are displayed as a flow chart in Figure 1, where the bracketed numbers correspond with the Statements in the Results of the phase two report (Bishop, Snowling, Thompson, Greenhalgh, and The CATALISE Consortium, 2017). In phase two the panel recommended that:

-

The diagnosis “Language Disorder” be used to refer to a profile of difficulties, associated with poor prognosis, that cause functional impairment in everyday life.

-

The diagnosis “Developmental Language Disorder” (DLD, with the social media hashtag #DevLangDis) be used when the language disorder was not associated with a known biomedical aetiology. Such aetiologies include, for example, autism spectrum disorder: ASD, language difficulties resulting from acquired brain injury: ABI, acquired epileptic aphasia in childhood, certain neurodegenerative conditions, genetic conditions such as Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, and oral language difficulties associated with sensorineural hearing loss.

- The diagnosis “Language Disorder associated with X” (with “X” representing one, or more, of the above conditions), be used when the language disorder was associated with a known biomedical aetiology, for instance, “Language Disorder associated with ABI” or “Language Disorder associated with Down syndrome and ASD” (see Bishop, 2017 for discussion).

It was further agreed that:

-

The (a) presence of neurobiological or environmental risk factors does not preclude a diagnosis of DLD. (b) DLD can co-occur with other neurodevelopmental disorders, and (c) DLD does not require a mismatch between verbal and nonverbal ability.

- risk factors might include, singly or in combination: family history, being male, living in poverty, having parents with low levels of education, and experiencing neglect or abuse.

-

other neurodevelopmental disorders may involve, singly or in combination, difficulties with Attention (e.g., ADHD), Motor function (e.g., dyspraxia/developmental coordination disorder, dysarthria), Literacy (see Snow, 2016 for discussion), Speech, Executive function, Adaptive behaviour, Behaviour problems, Auditory processing, and Intellectual function.

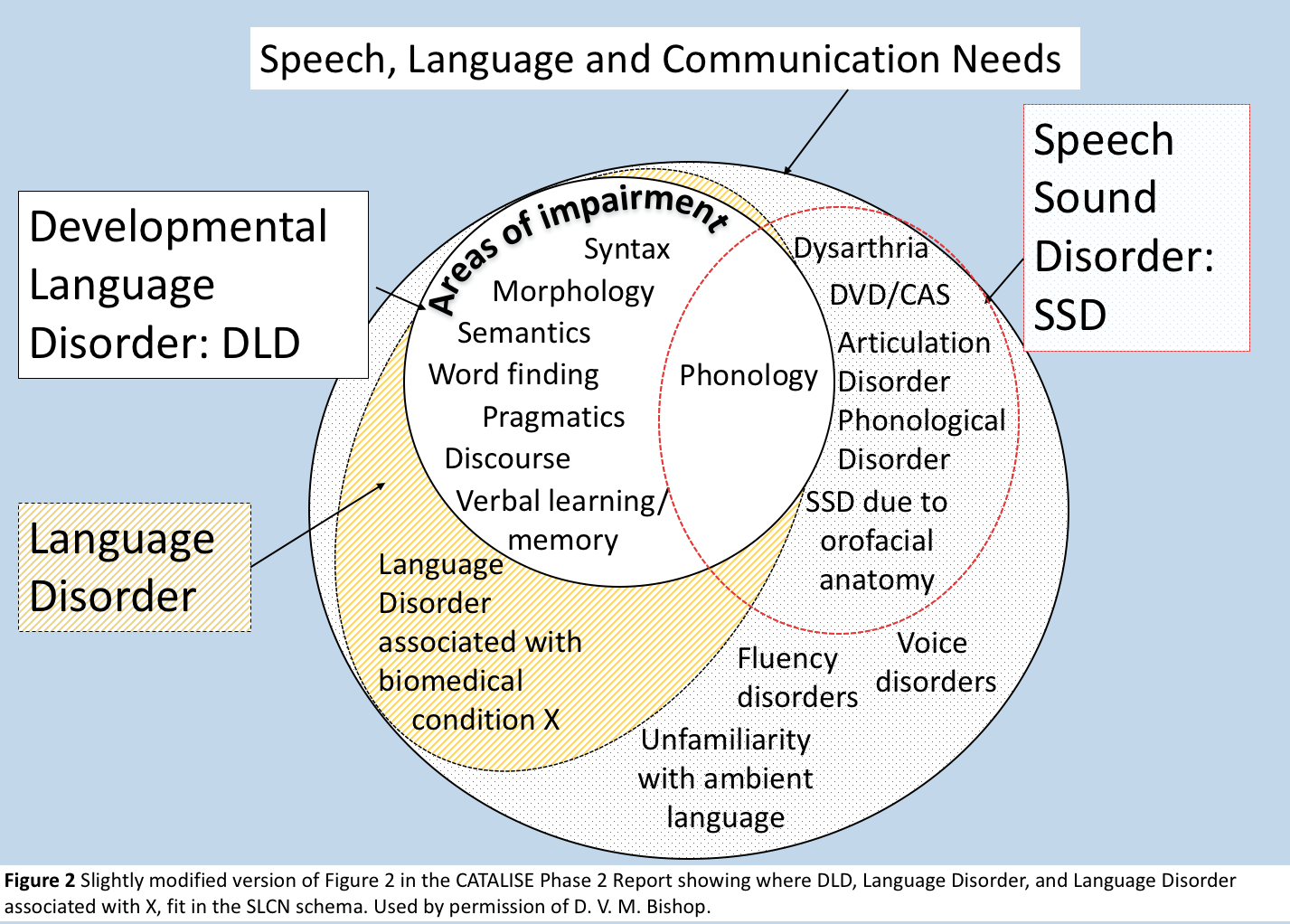

- The term Speech, Language and Communication Needs (SLCN) be retained as a broad category that includes all children with speech, language or communication difficulties, for any reason.

Speech Language and Communication Needs

Figure 2 is a slightly modified (by the author) version of a Venn diagram in Figure 2 in the CATALISE Phase 2 Report, showing where DLD, Language Disorder, and Language Disorder associated with X, fit in the SLCN schema. The term SLCN is most strongly associated with Care, Education and Speech and Language Therapy practice in the UK (Dockrell, Howell, Leung, and Fugard, 2017), Ireland (IASLT, 2017), and the Metropolitan Region of the Department of Education and Training in Queensland, with occasional use in New Zealand. It came as a surprise, therefore, to find it prominently displayed in Speech Pathology Australia's useful Speech Pathology in Schools document, released in November 2017, and citing the 2016 pre-print of a short report of a Delphi conducted in the Netherlands (Visser-Bochane, Gerrits, E., Reijnevel, and Van der Schans, 2017). Is the small SLT/SLP world shrinking?

A RCSLT revision of the Venn diagram includes “language difficulties in under-5s with few risk factors” in the white dotted area alongside fluency disorders, voice disorders, and lack of familiarity with the ambient language. This was a response to general concern among College members that these children, who take up many SLT hours, appeared to have been overlooked.

Dockrell, et al. (2017 p. 2) explain that in England, the 2001 Special Educational Needs’ (SENs) Code of Practice included a category “Communication and Interaction”, subdivided into SLCN and Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD). SLCN refers to children whose primary need is reflected in their oral language and excludes sensory impairment, cognition, ASD, or a specific learning difficulty. They note that educators and SLTs conceptualize the term differently from each other, with SLTs applying SLCN to a broader group of children (Dockrell, Lindsay, Roulstone, and Law, 2014), and that teachers greatly value profiling of a child’s difficulties, finding descriptions significantly more useful than a formal diagnosis. The 2001 categorization of SENs was retained in the 2015 revision of the code, which included a new requirement for health, education, and care personnel to work together to enhance joint outcomes (Department for Education, 2015).

“Language”

Communicating with teachers

Two speech-language pathologists, Patchell and Hand (1993) produced, for a readership of teachers, an easy-to-understand language disorders' explainer for the Independent Education magazine. The piece contains a simple description of the terminological barriers to teacher-SLP/SLT collaborative partnerships, which persist. Chief of these was teachers' and SLPs'/SLTs' different conceptualisations of the word “language”. Apart from the advice to “evaluate learning styles” (Howard Gardner's multiple intelligences work was popular in Education at the time, but see Gardner, 2003) the authors' advice for modifying teacher talk, and classroom work, to assist students with language disorders, are probably as useful to teachers now as they were a quarter of a century ago. The advice included a call for high school teachers to “routinely talk with significant others; parents, special education teacher, speech pathologist, counsellor etc. when students [with language disorders] have problems” (p. 7).

Communicating with families and interested others

If teachers and SLPs/SLTs unwittingly talk at cross purposes, mixing terminology in confusing ways, when they engage with families and others, communication will break down. Parents, media, and the public have an understanding of labels like ADHD, Autism, Cerebral Palsy, Down syndrome, Dyslexia, and Hearing Impairment, but despite its high incidence most have not heard of SLI. As terms, Language Disorder, and Developmental Language Disorder are more readily understandable for families, funding bodies, and decision-makers than “Specific Language Impairment” ... provided they know what “language” means in this context. All the more reason, then, for SLPs/SLTs to embrace the new terminology and actively raise awareness of DLD in the world community, including in the news, current affairs and social media.

Raising awareness of Developmental Language Disorder: #RADLD

The inaugural DLD Awareness Day, with the hashtag #DLD123, was on September 22, 2017. It was marked by functions at University College London, the University of Sydney, and other locations worldwide, and coincided with the publication of a special issue of the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry (JCPP), edited by Courtenay Norbury, devoted to DLD, a new video from the freshly re-badged Raising Awareness of Developmental Language Disorder (RADLD) campaign (formerly the RALLI campaign), featuring the unstoppable Eddie and Dyls, and another by the equally unstoppable Dorothy Bishop. Thanks to Becky Clark and others, the RADLD Campaign has a fun, informative and interesting YouTube channel, and tweets via @RADLDcam.

Hot on the heels of the awareness day, came the publication of the well-referenced, plain-English DLD page in Wikipedia, co-authored in true Wiki tradition (Bowen, 2012), by authorities in the field. It begins with a clear definition of the disorder:

“Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) is identified when a child has problems with language development that continue into school age and beyond. The language problems have a significant impact on everyday social interactions or educational progress, and occur in the absence of autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability or a known biomedical condition. The most obvious problems are difficulties in using words and sentences to express meanings, but for many children, understanding of language (receptive language) is also a challenge, although this may not be evident unless the child is given a formal assessment.”

Also in awareness-raising mode, Ebbels, McCartney, Slonims, Dockrell, and Norbury (in review, 2017) make a powerful case for evidence-based service delivery for children with language disorders. Their aims were to examine evidence of intervention effectiveness for children with language disorders at different tiers, and evidence regarding SLT roles; and to propose an evidence-based model of SLT service delivery. They write,

“... where prioritisation for clinical services is a necessity, we need to establish the benefits and cost-effectiveness of each contribution. Good evidence exists for SLTs delivering direct individualised intervention, and we should ensure that this is available to those children with pervasive and/or complex language impairments. In cases where service models are being provided which lack evidence, we strongly recommend that SLTs investigate the effectiveness of their approaches... Ineffective services are wasteful of limited resources and time (including the time of SLTs, parents, education staff, and the children themselves) and yet there is evidence that SLTs frequently fail to use evidence-based interventions, preferring to use their own local methods (Roulstone, Wren, Bakopoulou, Goodlad, and Lindsay, 2012). While clinical decisions may be a response to local need, resources, and priorities, SLTs should be clear how these differ from evidence-based interventions and collect data to establish whether they are effective in achieving their aims.” (p. 17). “Children with complex and pervasive language disorder and those with additional complex needs require the specialist skills of SLTs in order to make progress. SLTs need to have adequate time to work directly and collaboratively with these children, their families and educators, to improve their skills and reduce the functional impact of their language disorder.” (p. 18).

To DLD or not to DLD? That is the question ...

Of the MRA associations, the Irish Association of Speech and Language Therapists (IASLT), the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists (RCSLT), and Speech Pathology Australia (SPA) were quick to respond to the CATALISE recommendations, and ran with the new DLD terminology, preferring it to SLI. Speech-Language & Audiology Canada (SAC-OAC) and the New Zealand Speech-language Therapists' Association (NZSTA) were discussing possible “official positions” at the time of writing. The largest of the associations, the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) with its 191,500 members and affiliates, has not thrown its hat into the ring in an official sense, yet. There has been plenty of SLI vs. DLD discussion, however, among ASHA members, with billing codes and insurance pay-outs emerging as apparently intractable sticking points.

A rock and a hard place

“One of the difficulties with terms such as SLI and language delay is that they have literal interpretations that are not consistent with what we know about children with these problems.” Kamhi, 1998, p. 36

Unsurprisingly, private health insurers decide who will and will not be insured, who will and will not receive reimbursement for services, and for which diagnoses (or insurance codes), even when they do not fully understand the diagnostic nuances of disorders for which there is no biological test, like blood, urine, or chromosome studies. Similarly, public healthcare financing is driven by people who may not “know about” children with Language Disorders. As discussed above, Educators and SLPs/SLTs conceptualised “language” differently from each other (Patchell and Hand, 1993), and there are significant differences in terminology-related practical considerations for speech-language professionals in different parts of the world. An example of the latter is the parting of the ways between “Developmental Verbal Dyspraxia” (DVD) the term used in the UK and recommended by the RCSLT, and “Childhood Apraxia of Speech” (CAS) the term used in the US and recommended by ASHA, because US insurance companies do not pay out for anything earmarked "developmental". “Childhood” is insurance-friendly; “Developmental” is not, even though “childhood” indicates that a disorder becomes apparent in childhood, and “developmental” indicates exactly the same thing.

Australian, British, Canadian, Irish, and New Zealand motor-speech disorders' researchers can, and do, use “CAS” in their publications, and clinicians can use it in all facets of practice, partly because there are no potentially undesirable repercussions for clients if they do (and also because they wish to support the cause of consistent terminology across national boundaries), but the reverse is not true. You just don't find American clinicians, or academics using “DVD”, with only a smattering of them using “DLD” at this time. Fortunately, that does not mean that there are no signs of change. For example, it is heartening to see @ASHAjournals and @SIGperspectives Tweeting the hashtag #DevLangDis, and @s_redmondUofU, @mcgregor_karla, @Shar_SLP, @SlpSummer, @kimberlyslp, @hstorkel, @ecoleSLP, @lfinestack, @TELLlab, @9wyneth, @kush_stephanie, @staceypalant, and other ASHA members with #DevLangDis or #DLD123 in their Twitter bios.

Clinicians in private practice in the States are between a rock and a hard place in deciding whether to stay with SLI or to transition to DLD as their preferred diagnostic term. They want to serve their clients responsibly, effectively and ethically, and as part of that process they will want to ensure that they tick all the boxes so that their clients (or their parents) receive unambiguous invoices and timely reimbursement. They may also believe that “terminology is important for more than insurance coding. It's also important for self-advocacy, arguing for increased research dollars, and for identifying reliable treatments/approaches to resolving the challenges posed by the disorder” (Sean Redmond, Language Section Editor-in-Chief, JSLHR, personal correspondence, Nov 7, 2017).

Ethical practice and evidence-based practice are inseparable. If practitioners infer from the literature that lack of consensus about terminology leads to confusion and impedes both research and children's access to appropriate services (Bishop, 2014), and they simply like the CATALISE recommendations, then they might feel the urge to join the majority (of associations; not the majority of SLPs at this point) and apply DLD as a diagnosis. But if they do, the financial penalty for clients is instantaneous. In turn, their incomes are set to suffer as the word gets around that the SLP concerned does not apply “conducive”, insurance-friendly terminology.

DLD, DVD, SLI and CAS are abbreviations for communication disorders that do not dissipate over time; they can be managed and ameliorated with appropriate intervention, but they persist for a lifetime. Most researchers and practitioners will agree that DLD cannot be “cured”, and language “normalised” through therapy. Rather, clinicians aim realistically, without setting their sights too low by underestimating what they and the child can do, to improve functioning, while acknowledging that the forecast is for long-term difficulties.

Wishlist

Webwords' wishlist for the near future is to see:

- The professional associations, ASHA, NZSTA, SAC-OAC, and others, embrace and endorse the new DLD terminology, as IASLT, RCSLT and SPA have done, encouraging their members to use it.

- Inclusive, open discussion between stakeholders, about intervention goals and expectations. Should the primary goal for children with DLD be to narrow, or even close, the gaps between their language performance and that of typical peers, or should we be focusing on achievable, functional outcomes? If yes, how should those outcomes be measured, and what should the (collaborative) professions be saying to families?

- The unhelpful delay vs. disorder dichotomy being shown the door.

- Political lobbying, at the local, national and international levels, for better provisioning for children, young people, and adults with DLD.

- Increased understanding of DLD and its implications, including general community awareness that early literacy difficulties and language disorder are highly correlated.

For the medium-term:

- Research, including high quality Randomised Controlled Trials where practicable, leading to clearer pictures of: what “effective” intervention looks like; the impact of DLD on children (Levickis, Sciberras, McKean, Conway, Pezic, Mensah, Bavin, Eadie, and Reilly 2017); the impact of DLD in adulthood; and when in development intervention will have most impact. Is there an age, stage or window in which children will progress “faster” in response to intervention? Is there a critical level of intervention: what dosage (frequency and intensity) of intervention is optimal?

- Research into intervention with children with DLD associated with comorbidities, and children with low IQs; and, more collaborative research partnerships between clinicians, educators, psychologists and researchers.

- Research studies of the cascading effects of language therapy on other areas of development and function; for example, does language intervention improve social, emotional and behavioural functioning (Levickis, et al., 2017)?

For the longer term Webwords would like to see:

- Research literacy as a “given” attribute of all members of the profession, wherever and whenever they trained. Only SLPs/SLTs who are critical consumers of research are in a position to clearly understand intervention studies and to see their applicability to practice. This means that all training institutions must include research methodology, experimental design, statistics and logic in their curricula, in sufficient depth.

- Improved ease of access, for clinicians, to free or affordable high quality research.

- Time to read new literature timetabled-in to practitioners' workload, and not something that has to be done after-hours.

A well-known quotation, usually attributed to Margaret Mead, goes:

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.” Margaret Mead (cited by Lutkehaus, 2008)

Philosopher Joshua A. Miller's entertaining reworking of it is in Figure 3, and related discussion is in his blog11, where he writes:

"Paying attention to the effects of small-group politics seems naive, since big, impersonal social forces probably have more impact on outcomes. Academic “realism” marginalizes human agency. But small-group politics is morally important–it’s what we should do. It’s also more significant than the “realists” believe, although less powerful than Margaret Mead implied." Miller, 2011

Strategic lobbying

Webwords has one more wish (for now) and that is for:

- SLPs/SLTs to be more politically astute, active, and aware of opportunities to impact public policy, and more actively supportive of those who are already trying.

The CATALISE Delphi provides the perfect springboard for effective lobbying, which would see the profession, globally, and its agents applying a range of strategies designed to develop and/or realign policy around DLD, by influencing government (including regulators), consumers, and the public.

References

Bishop, D. V. M. (2014). Ten questions about terminology for children with unexplained language problems. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 49(4), 381-415. FULL TEXT

Bishop, D. V. M. (2017). Why is it so hard to reach agreement on terminology? The case of developmental language disorder (DLD). International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 52(6), 671-680. FULL TEXT

Bishop, D. V. M., Snowling, M. J., Thompson, P. A., Greenhalgh, T., & The CATALISE Consortium. (2016). CATALISE: a multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study. Identifying language impairments in children. PLOS One, 11(7), e0158753. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0158753 FULL TEXT

Bishop, D. V. M., Snowling, M. J., Thompson, P. A., Greenhalgh, T., & The CATALISE Consortium. (2017). Phase 2 of CATALISE: a multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language development: Terminology. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0158753 FULL TEXT

Bowen C. (2012). Webwords 44: Life online. Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech-Language Pathology, 14(3), 149-152. WEB PAGE PDF

Cole, Z. D., Donohoe, H. M., & Stellefson, M. L. (2013). Internet-Based Delphi Research: Case Based Discussion. Environmental Management, 51(3), 511-523. FULL TEXT

Department for Education. (2015). Special Educational Needs and Disability Code of Practice 0 to 25 Years. Statutory Guidance for Organisations which Work with and Support Children and Young People who have Special Educational Needs or Disabilities. FULL TEXT

Dockrell, J. E., Howell, P., Leung, D., & Fugard, A. J. B. (2017) Children with Speech Language and Communication Needs in England: Challenges for Practice. Frontiers in Education 2:35. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00035 FULL TEXT

Dockrell, J., Lindsay, G., Roulstone, S., & Law, J. (2014). Supporting children with speech, language and communication needs: an overview of the results of the Better Communication Research Programme. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 49(5), 543–557. FULL TEXT

Ebbels, S. (2014) Introducing the SLI debate. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 49(4), 377-380. FULL TEXT

Ebbels, S. H., McCartney, E., Slonims, V., Dockrell, J. E., & Norbury C. (2018). Evidence based pathways to intervention for children with language disorders. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, xx. FULL TEXT

Ervin, D. A. & Merrick, J. (2014). Intellectual and Developmental Disability: Healthcare Financing, Frontiers in Public Health, 2(83), 1-8. FULL TEXT

Gardner, H. (2003). Multiple Intelligences after Twenty Years. Invited Address, American Educational Research Association, April 21, 2003. FULL TEXT

IASLT (2017). Supporting Children with Developmental Language Disorder in Ireland; IASLT Position Paper and Guidance Document. FULL TEXT

Kamhi, A. J. (1998). Trying to make sense of developmental language disorders. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 29(1), 35-44. FULL TEXT

Levickis, P., Sciberras, E., McKean, C., Conway, L., Pezic, A., Mensah, F. K., Bavin, E. L., Bretherton, L., Eadie, P., Prior, M., & Reilly, S. (2017). Language and social-emotional and behavioural wellbeing from 4 to 7 years: a community-based study. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-1079-7 FULL TEXT

Lutkehaus, N. C. (2008). Margaret Mead: The Making of an American Icon, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, p. 261.

Patchell, F. & Hand, L. (1993). An invisible disability - Language disorders in high school students and the implications for classroom teachers. Independent Education. 12, 30-36. FULL TEXT

Roulstone, S., Wren, Y., Bakopoulou, I., Goodlad, S., Lindsay, G. (2012). Exploring interventions for children and young people with speech, language and communication needs: A study of practice. London: Department for Education. FULL TEXT

Snow, P. C. (2016). Language is literacy is language. Positioning Speech Language Pathology in education policy, practice, paradigms, and polemics. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 18(3), 216-228. FULL TEXT

Visser-Bochane, M. J., Gerrits, E., Reijneveld, S. A., & Van der Schans, C. P. (2017). Atypical speech and language development: A consensus study on clinical signs in the Netherlands. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 52(1), 10-20. FULL TEXT

Links

ASHA: Speech-Language Pathology Medical Review Guidelines: 2015

DLD and Me

DLD and Me: The Many Terms Used for Developmental Language 🆕

Developmental Language Disorder: A public health problem? PDF

Dyslexia and developmental language disorder: same or different? - Maggie Snowling

Facebook Page: Moor House Research and Training Institute

Facebook Page: Raising Awareness of Developmental Language Disorder RADLD

NAPLIC's compilation of DLD online articles/information/awareness-raising resources

Oxford Study of Children's Communication Impairments

Padlet Page: DLD - Natalie Munro

Prisons, developmental language disorder, and base rates

Raising Awareness of Developmental Language Disorder RADLD

The IJLCD Winter lecture: Dorothy Bishop: Why is it so hard to agree on definitions and terminology for children's language disorders?

Twitter Feed: Raising Awareness of Developmental Language Disorder RADLD

Commentary

December 1, 2018 ASHA Leader: Diverging Views on Language Disorders ~ Nancy Volkers

December 1, 2018 ASHA Leader: Does an SLI Label Really Restrict Services? ~ Nancy Volkers

Webwords 35: November 2009: Wednesday's Child

Monday's child is fair of face,

Tuesday's child is full of grace,

Wednesday's child is full of woe,

Thursday's child has far to go.

Friday's child is loving and giving,

Saturday's child works hard for a living,

But the child born on the Sabbath Day,

Is fair and wise and good and gay. Mother Goose

Beautiful Val was uncontainable when she brought four-year-old Timothy to his Wednesday speech appointment several weeks ago. Interrupting constantly with peals of appreciative laughter - in response to her own witticisms and asides - she disrupted the session to the point that persisting was futile.

"Oh God, I'm terrible, terrible, terribly terrible" she chortled unrepentantly, flicking her perfectly coiffed hair with impeccable, fluttering French Tips. "I promise to be good next time. Best behaviour." Even in this loud, agitated, witty state there was something brittle about her. A needy, vulnerable fragility.

She switched topic unexpectedly, exploding into song to the tune of I'm getting married in the morning, "I'll make a motza minta money, when I buy those fresh food people shares; pull out the stopper, let's have a whopper! But get me to the Broker on time!" The melody changed to a familiar supermarket refrain. "Oh! Woolworths the fresh food people, get me to the Broker on time." She stopped. "Would Woolies be one ell or two? Two would be a jumper, wouldn't it? Warm woollies from Woolies. My English Dad always talked about his woollies. Winter woollies. Tepidus vestio; valde tepidus ornatus - he was a Classics scholar, you know! Latin, Greek, Hebrew, not Yiddish. Anyway, with those shares I'll be a rich wo-MAN." New tune. It took me back to 1976, Fiddler on the Roof and my unforgettable first encounter, as a speech-language pathologist, with a family in which the mother had a mental illness. I remembered her name, and the child's, and the father's. Alison and Lindsay, and Ben aged three. And there was a baby.

"If I were a rich man,

Ya hadeedle deedle, bubba bubba deedle deedle dum.

All day long I'dbiddy biddy bum.

If I were a wealthy man.

I wouldn't have to work hard.

Ya ha deedle deedle, bubba bubba deedle deedle dum.

If I were abiddy biddy rich,

Yidle-diddle-didle-didle man."

Timothy looked at me imploringly with a face that said, "Make her stop!"

"Do you know what the midwife said to my Dad when I was born? She told him I was strong and healthy, and he said, 'then she shall be called Valerie'."

"Is that what Valerie means?"

"Well, yes, in Latin, but obviously, OBVIOUSLY, it's a joke, a nonsense..." shrieked Val. "A paradox, a contradiction, an absurd and illogical inconsistency, a cruel and ironic joke...a mad misnomer...oh God, you know...with my mental health issues...you know, iss - youse...are youse having iss - youse?"

She continued talking and singing incessantly, ideas and neologisms flying, as worried, over responsible little Timothy propelled her out the door. I wondered about his mental health, now and in the future.

A STATE OF WELL-BEING

Mental health is defined in the section of the WHO web site devoted to such matters as a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community. Elsewhere on the web, in dictionaries and encyclopaedias it is described as a state of emotional and psychological well-being in which an individual is able to use his or her cognitive and emotional capabilities, function in society, and meet the ordinary demands of everyday life.

FULL OF WOE

The following week saw a different Val, medicated to the hilt. Still beautiful, with that indefinable frailty, the French Tips had been gnawed to nothing, the hairdo was awry and she drooped into the room - a picture of defeat. Timothy, hair lank and knotted, clothes grubby and breath sour, followed her closely: casting sad, apprehensive eyes around the room, slumping into a chair, bearing his unpredictable world on his shoulders. Wednesday's mother; Wednesday's child. "Mine Nan bring me d-nuther day. Mine Nanny Sylvia. Mummy go hos-pul get better again. Mummy come back." He hugged himself for reassurance. "Yes," she said expressionlessly to herself, self-absorbed, without looking at him or at me. "I'll be back."

TOGGLING BETWEEN WINDOWS

Timothy and his grandmother arrived bright and early the following week, both bandbox fresh, enjoying each other's company. Sylvia and I were probably both thinking that this was the fifth time we had met and that each time was because Val was having treatment. The first time had been when Timothy presented initially as a non-verbal two year old. Sylvia explained that Val would be bringing him to therapy in due course, but not for a while because she had postpartum depression and wasn't up to it. Surprisingly, in rapid succession over just eighteen months, Val's psychiatric diagnosis had been changed to chronic depression and then, soon after her husband left and filed for divorce, bipolar disorder. She was in and out of hospital repeatedly, and, as she put it, "Toggling between windows". When I asked what she meant she responded that life, frankly, for her was either at a distance, through a window on the world clouded by mood stabilizing medications and deep malaise, or up close and extreme. The view from this second, exciting window was intensified by manic mood swings and (usually) a refusal to medicate.

MATERNAL DEPRESSION

The incidence of depression in all women is reported to be between 10 and 12%. This figure skyrockets to at least 25% for low income women. Exposure to maternal depressive symptoms, whether during the prenatal period, postpartum period, or chronically, has been found to increase children's risk for later cognitive and language difficulties (Sohr-Preston & Scaramella, 2006). Indeed, depression is a significant problem among both mothers and fathers of young children. Intriguingly it has a more marked impact on the father's reading to his child (as opposed to mothers' reading) and, subsequently, the child's language development (Paulson, Keefe & Leiferman, 2009).

Classically, depressed mothers are seen as "under stimulating", being less involved than well mothers, or inconsistently nurturing with their children (Field, 1992). They have been found to:

- initiate parent-child interactions less frequently than non-depressed mothers and not get as much pleasure from them;

- talk less to their infants;

- have reduced awareness of and responsiveness to their infants' cues;

- rarely, if ever, use child directed speech ("parentese");

- be slow to respond to their children's overtures for verbal or physical interaction;

- make overly critical comments and criticise more frequently;

- show difficulty in fostering their children's speech and language development;

- experience trouble asserting authority and setting limits that would help the child learn to regulate his or her behaviour; and

- find it hard to provide appropriate stimulation.

By contrast, some depressed mothers interact excessively, over stimulating their infants and causing them to turn away. Whether under or over stimulating, these mothers are not responding optimally to their infants' cues or providing a suitable level of feedback to help their children learn to adjust their behaviour. Additionally, there is evidence to show that the children of depressed mothers mirror their mothers' negative moods and are overly sensitive to them (Goodman & Gotlib, 2002). Some mothers envelop their children in an inappropriate closeness and over-identification with their own moods. Children who are preoccupied with and invested in the reactions of their mothers, fathers or other caregivers may not learn to seek out comfort or accept consolation or reassurance when they need it. As a result, their own activity and ability to express emotion may not develop adequately.

ANOTHER STORY

Of course it is impossible to predict how the story of Val and Timothy will unfold, but hopefully it will not be as tragic as the 1976 story of Alison, Lindsay, Ben and the baby. When Alison brought Ben for a speech assessment the three weeks old baby, there in a corner in a carry cot, had not been named. I was concerned when Alison told me dully that she had not had the energy to talk to Lindsay properly about a name for "it", and the perfunctory, disinterested way she dealt with the tiny infant's survival needs. She told me she would be all right when the baby blues had passed, as they had done months after Ben's birth. But this was more than the blues, it was more like postpartum depression. She was off her food, wasn't sleeping, was irritable with intense angry outbursts, and overwhelmingly tired. As the weeks passed she told me that she was not bonding with "it" (Jessica) and that she was having troubling fantasies about harming herself and the baby. At the time I shared rooms with a psychiatrist, and a meeting with him for Alison and Lindsay was quickly organised. Once on medication she seemed better, but still something was not quite right. Towards the end of Ben's therapy block Lindsay rang to cancel his last three appointments, explaining that they had had "a family calamity". I left the door open, not daring to guess what the calamity was. When Ben resumed his intervention, there was no Alison and no baby. She had smothered the infant and taken an overdose.

JUST SIMPLY ASK

Debriefing was hard. The psychiatrist said I had done the best one could do by facilitating the referral, and I told him I knew he had done all he humanly could. It was unsatisfactory and sad. His advice to me at the time has been integrated into practice over several decades. "Ask," he said, "When you take a history, ask each Mum, or Dad, or other primary caregiver who accompanies new clients, as a matter of routine, about his or her state of mind. Don't try to look for tell-tale signs or red flags in a history. Just simply ask."

This good advice is to be had everywhere in the Internet era on a wide range of web sites. It can be found in the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2009) recommendations for the routine screening of adults for depression, where health professionals are advised to ask two basic questions that may lead to appropriate referrals:

1. "Over the past two weeks, have you felt down, depressed or hopeless?" and

2. "Over the past two weeks, have you felt little interest or pleasure in doing things?"

If an adult client answers "yes" to either or both questions they should be referred, according to the Task Force, to an appropriately qualified professional in the mental health field to be guided through an in-depth questionnaire to rule depression in or out.

The panel did not make a comparable recommendation for (or against) routine screening of children (7 to 11 years) and adolescents (12 to 18 years) for depression, citing a lack of evidence about the reliability and efficacy of such tests in youngsters.

Speech-Language Pathologists working with young children should know that a loss of interest in play is a red flag that a child of three to six years of age is depressed, and that two other major warning signs are sadness and irritability (Luby, et al., 2003).

REFERENCES

Field, T. (1992). Infants of depressed mothers. Infant behavior and development, 18(1), 1-13.

Goodman, S. H. & Gotlib, I. H. (2002) (Eds.), Children of Depressed Parents: Alternative Pathways to Risk for Psychopathology, Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press.

Luby, J. L., Mrakotsky, C., Heffelfinger, A., Brown, K., Hessler, M., & Spitznagel, E. (2003, June). Modification of DSM-IV Criteria for Depressed Preschool Children, American Journal of Psychiatry, 160,1169-1172.

Paulson, J. F., Keefe, H. A., & Leiferman, J. A. (2009). Early Parental Depression and Child Language Development, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(3), 254-262. ABSTRACT

Sohr-Preston, S. L. & Scaramella, L. V. (2006). Implications of Timing of Maternal Depressive Symptoms for Early Cognitive and Language Development, Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 9(1), 65-83. ABSTRACT

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2009). Screening and Treatment for Major Depressive Disorder in Children and Adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Pediatrics, 123,1223–28.

LINKS

- APA: Stress

- APS: Mental Health

- Illness stops 650,000 older Aussies

- The Lancet: global mental health

- WHO Mental Health

Webwords 59: Mental health: How are they now? - November 2017

Remember the Australian Communication Quarterly and ACQ, the forerunners of JCPSLP? Exactly eight years ago, ACQ's November theme was Mental Health, and it contained Webwords 35: Wednesday's Child. The child was my four-year-old client Tim, who attended many of his Wednesday sessions with his maternal grandmother Sylvia, because his mother Val was either receiving help as a psychiatric unit in-patient or was too unwell to venture from home. Revisiting Tim's story, and the sad story of Alison (d) and Lindsay, and their children Ben aged four—my client in 1976—and baby Jessica (d), coincided with the August 2017 first screening of The Bridge in the ABC's reality TV series Australian Story. Together, the three stories evoked vivid memories of all the players in Tim's and Ben's stories, one of whom was Alison's psychiatrist, with whom I shared professional rooms. In the days following Alison and Jessica's murder-suicide, he volunteered one of the best, and most acted upon, pieces of advice about screening adults for depression that I received in over four decades of clinical practice.

"Ask," he said, "When you take a history, ask each Mum, or Dad, or other primary caregiver who accompanies new clients, as a matter of routine, about his or her state of mind. Don't try to look for tell-tale signs or red flags in a history. Just simply ask [two basic questions that may lead to appropriate referrals]."

1. "Over the past two weeks, have you felt down, depressed or hopeless?" and

2. "Over the past two weeks, have you felt little interest or pleasure in doing things?"

I wondered if anyone asked Donna Thistlethwaite those, or similar questions in the two weeks before her Australian story unfolded, and how she might have replied. Or was everyone just telling her she was fabulous, encouraging her not to be silly, or employing the wrong kind of kindness, when she tried to confide her fears and insecurities?

A confluence of miracles

The Bridge is an unsettling portrayal of Donna Thistlethwaite's 7-to10-day plummet from an apparently confident high-achiever in HR, to the depths of self-doubt and hopelessness, culminating in a desperate, suicidal 40 metre leap into oblivion from the Story Bridge on the Brisbane River. Her partner, son, work colleagues, and the world in general, she thought bleakly, would be better-off without her, with her floundering attempts to return to the workforce after 14 months' maternity leave, to lead a team, and come to grips with an intimidating new IT system. Oblivion was not the outcome. Her fortuitous rescue, by two decisive Brisbane CityCat crew while responsible for a full load of passengers—in 2012, a year that saw 15 other people die because of the same fall—was described in the program as 'a confluence of "miracles"', and a new chance at life.

A key theme of the story was that destructive, depressing anxious thinking can lead to suicidal thoughts, even in people, like Donna, with no history of the types of mental illness generally associated with suicide risk. In the telling, there was no suggestion that she might have had postpartum depression or perinatal mood disorder, which are in the DSM-5 and the ICD, but not as diagnoses that are separate from depression; or Imposter syndrome, which, although it generates fascinating research activity, is neither a syndrome nor a diagnostic entity.

The imposter phenomenon

Impostor syndrome, or less fancifully, the imposter phenomenon, is observed in high-achieving individuals who dismiss or minimise their obvious accomplishments self-deprecatingly as unworthy flukes, and pale imitations of what others in the same field have achieved, while fearing being exposed as fakes, undeserving of any admiration and accolades for their outward successes. Unlike real imposters, who practice deception as assumed characters, or under false identities, names or aliases, an individual experiencing the imposter phenomenon has chronic feelings of self-doubt, genuinely dreading being found out as an intellectual fraud.

In his blog, Hugh Kearns defines it as, 'The thoughts, feelings and behaviours that result from the perception of having misrepresented yourself despite objective evidence to the contrary.' Like Kearns, Dr Amy Kuddy—she of the second-most viewed TED Talk of all time—has experienced the phenomenon. In an excerpt from her book, Presence (Kuddy, 2015), she writes, 'Impostorism causes us to overthink and second-guess. It makes us fixate on how we think others are judging us (in these fixations, we’re usually wrong), then fixate some more on how those judgments might poison our interactions. We’re scattered—worrying that we underprepared, obsessing about what we should be doing, mentally reviewing what we said five seconds earlier, fretting about what people think of us and what that will mean for us tomorrow.'

Investigators who conducted an American pilot study of 138 medical students, Villwock, Sobin, Koester, and Harris (2016) demonstrated, via a self-administered questionnaire: The Young Imposter Quiz, a significant association between imposter syndrome and the burnout components of physical exhaustion, cynicism, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization, with 49.4% of the female students, and 23.7% of the males experiencing the imposter phenomenon.

The phenomenon, much discussed in Reddit by SLPs/SLTs and students (e.g., Reddit: [Seeking Advice] Sometimes I feel like a bad clinician and Reddit: [Seeking Advice] How did you get over imposter syndrome in graduate school?) goes hand-in-hand with maladaptive levels of perfectionism (Beck, Seeman, Verticchio, & Rice, 2015) and stress. In a related study, Beck, Verticchio, Seeman, Milliken, & Schaab, (2017) looked at the effects of a mindfulness practice, comprising yoga and simple breath and body awareness techniques, over the course of a university semester, on participants' levels of self-compassion, perfectionism, attention, and perceived and biological stress. The 37 volunteer participants (19 undergraduate CSD students and 18 SLP graduate students) were all females, and aged between 18 and 26 years. Comparing the mindfulness group with a control group, the investigators found that their perceived stress levels and potentially negative aspects of perfectionism decreased and biological markers of stress and self-compassion improved. Experimental participants' reflective writings indicated they perceived the sessions to be beneficial, but no significant effect was found for attention. Beck et al. concluded, "College life can be stressful, and the belief that one needs to be perfect might exacerbate stress. To best assist our students, instructors and supervisors must be aware of students whose behaviors are indicative of high stress levels and maladaptive aspects of perfectionism. Although some students might require intervention from mental health professionals, there are steps that instructors and supervisors can take to facilitate students' overall well-being..." (pp. 12-13).

Overall well-being: Are Val and Tim OK?

Towards the end of 2010, Timothy was discharged from SLP intervention with age-typical speech and language skills. Val brought him to most of his sessions that year, appearing happier, more settled, and more able to enjoy his company all the time. Sylvia was a rock for both, remaining supportive and involved, minding Tim when Val had psychiatry and clinical psychology sessions and peer support meetings organised through the former NSW Depression and Mood Disorders Association (DMDA), which was active from 1981 and 2012, then becoming Bipolar Australia.

I asked her whether there have been a distinct turning-point. 'Two things', she said, 'First, getting a definite diagnosis after all that chopping and changing. And this...'. She reached into her bag and drew out a small card on which she had written, 'Recovery is possible for anyone affected by Bipolar Disorder, when they are empowered to help themselves and others through person-to-person centred communication'. I read that in a DMDA pamphlet and it gave me so much hope that I've carried around ever since. There's no magic formula; I miss the highs and I still have the odd dark day, but with the psychs, peer support from friends in the same boat and the members of my support group, family education—especially for Tim, mum and dad, and my ex—and taking the meds—I'm good, really quite good.' 'And Sylvia, how is she?' 'Well, that's where I feel guilty. I wouldn't say my illness broke mum and dad, but it put a huge strain on their marriage. The problem was that mum "got it" and dad didn't really believe in bipolar and resented the time she devoted to caring for us when they could have been enjoying their retirement, going for trips together, and that sort of thing. But they have all that sorted now I'm better. And we're all terribly proud of the way Tim is doing at school and everything.' 'Everything?' 'Yes, everything.'

References

Beck, A., Seeman, S., Verticchio, H., & Rice, J. (2015). Yoga as a technique to reduce stress experienced by CSD graduate students. Contemporary Issues in Communication Sciences and Disorders, 42, 1–15. Retrieved August 15, 2017 from www.asha.org/Publications/cicsd/default/

Beck, A. R., Verticchio, H., Seeman, S., Milliken, E., & Schaab, H. (2017). A Mindfulness Practice for Communication Sciences and Disorders Undergraduate and Speech-Language Pathology Graduate Students: Effects on Stress, Self-Compassion, and Perfectionism. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, doi:10.1044/2017_AJSLP-16-0172.

Bowen, C. (2009). Webwords 35: Wednesday’s Child. ACQuiring Knowledge in Speech, Language and Hearing, 11(3), 155-156.

Kuddy, A. (2015). Presence, Bringing Your Boldest Self to Your Biggest Challenges. New York: Little, Brown & Company.

Villwock, J. A., Sobin, L. B., Koester, L. A., & Harris, T. M. (2016). Impostor syndrome and burnout among American medical students: A pilot study. International Journal of Medical Education, 31(7), 364-369.

Links

10 ways of overcoming imposter syndrome

Australian Psychological Society

Bipolar Australia

Bipolar Caregivers

Defeating self-sabotaging behaviour

Heywire: Mental Health

Intellectual Disability Mental Health

Mayo Clinic: Postpartum depression

NHS: Twitter The Mental Elf @Mental_Elf

NHS: Youth mental health

NIH: Bipolar disorder

Speech, language and communication and mental health: A complex relationship

New York Times: Disability

ReachOut Australia: Perinatal depression

ReachOut Australia: What are mental health issues?

Rural and Remote Mental Health

SANE Australia

WHO: Mental health

Webwords 35, November 2009 Wednesday's child

Why Getting compliments can be so embarrassing